So the Potomac River took a gut punch on January 19 when a 72-inch section of the ancient Potomac Interceptor sewer line collapsed near Clara Barton Parkway in Montgomery County, Maryland. Roughly 240–300 million gallons of untreated sewage found its way into the C&O Canal and then the river before bypass pumps kicked in and stopped the worst of it by early February. For us Potomac River boaters, this is the kind of news that makes you double-check your shrink-wrap and reach for another hot toddy. But before ya start polishing the brass in mourning, remember that this is February, and our real boating season doesn’t even crank up until May, which is plenty of time for Mother Nature (and a few trillions of gallons of fresh river water) to do her thing!

Independent testing by the Potomac Riverkeeper Network and University of Maryland researchers painted the early dismal picture: on January 28, E. coli at the Lock 10 sewage effluent site was a staggering 2,731 times above the safe recreational limit of 410 MPN/100 mL. By February 3 it had climbed to 4,227 times over at the same spot. Contamination stretched about 10 miles downstream to Thompson Boat House in D.C., with levels still 2–59 times above safe at points along the way. Staphylococcus aureus and even MRSA turned up at the source, with staph showing up at one-third of downstream sites. (Full details at potomacriverkeepernetwork.org/press-release-dc-sewer-spill-monitoring).

Virginia Department of Health wasted no time issuing a recreational advisory, without any of their own testing, on February 13 that covers a whopping 72.5 miles of the main-stem Potomac, from the American Legion Bridge (I-495) all the way down to the Governor Harry W. Nice Bridge (Route 301). Check the latest at vdh.virginia.gov/news/potomac-sewage-spill.

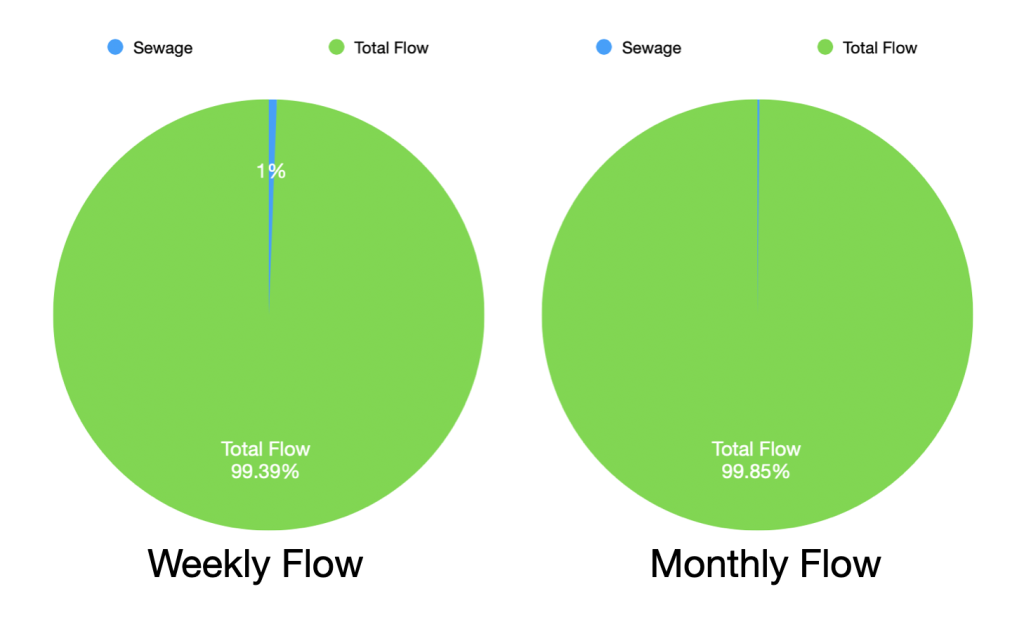

On an average day the Potomac pushes about 7 billion gallons of water past Washington, so even a 300-million-gallon spill gets diluted fast once the flow is rerouted.

On an average day the Potomac pushes about 7 billion gallons of water past Washington, so even a 300-million-gallon spill gets diluted fast once the flow is rerouted. We have seen a temporary bump in high bacteria numbers north of the Wilson bridge, but history and current testing shows those spikes should drop off quick once the fresh water really starts moving. As of today, it has been 11 days since any discharge has occured at that location.

Of course the media is eating this up (gross). By watching the news reports, you’d swear a person could catch river-AIDS by just looking at the water! It’s true – fear sells, and everyone is looking to cash in. So chin up! It’s only mid-February, nobody’s swimming or rafting up right now anyway, and we’ve got two full months before the first buds pop and the first beer hits the fuel dock.

By the time we’re firing up the engines for the 2026 season, this mess will be ancient history and the river will be back to its not-sparkling self again. In the meantime, keep an eye on the official updates, give the media alarmists a wide berth, and start planning that first spring cruise to Belmont Bay or Holiday Island. Remember, the river keeps flowing into the Chesapeake, and not up into the tributaries like the Occoquan and Mattawoman Creek. The Potomac has seen worse and bounced back stronger, same as us. Fair winds, clean bottoms, and see you on the water in May!

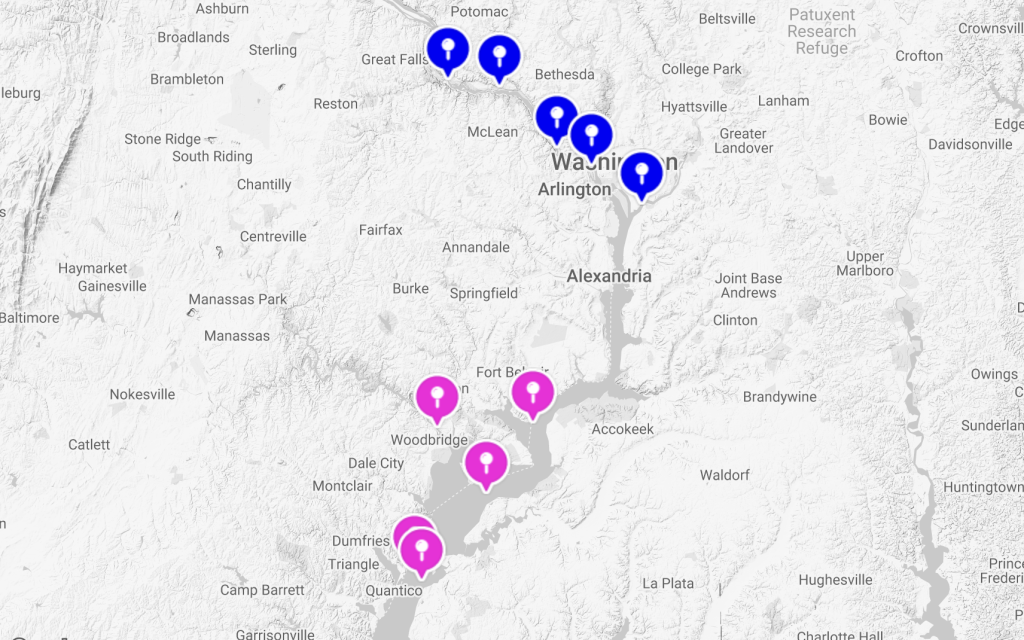

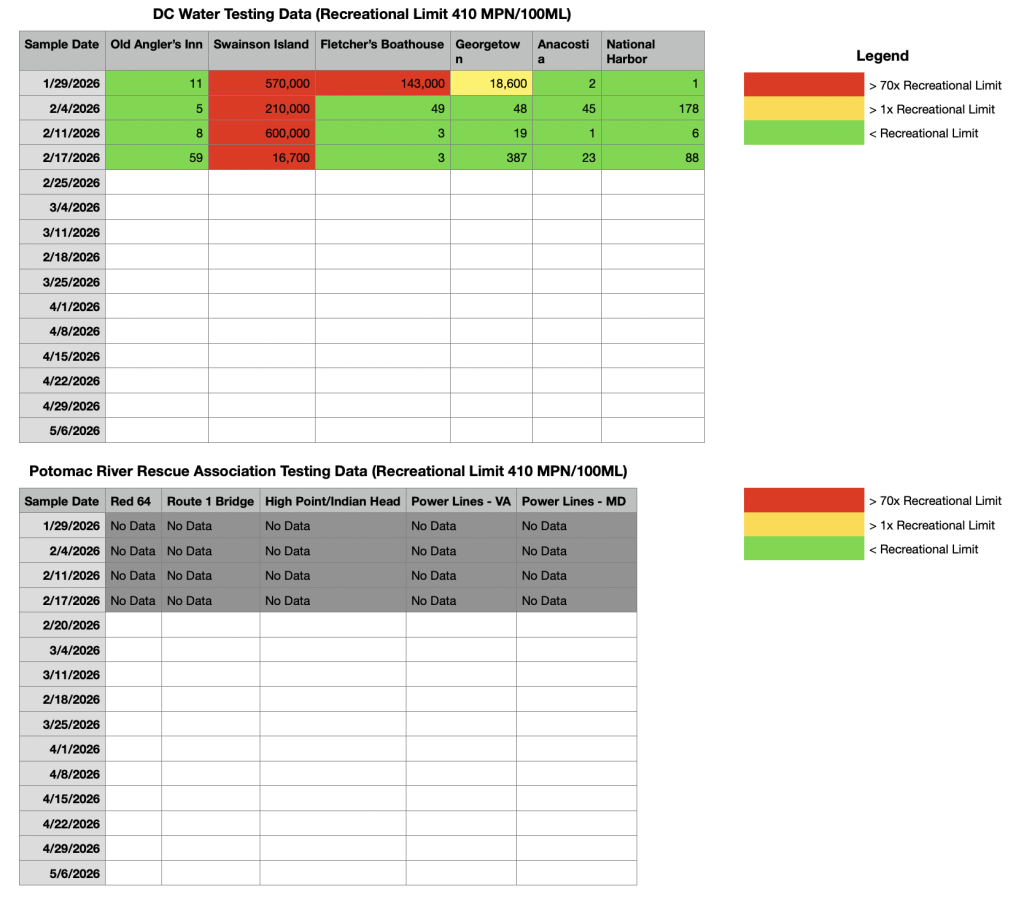

Check back here for ongoing coverage of E. coli testing numbers from DC Water and Potomac River Keeper Network (blue), and the Potomac River Rescue Association (purple). We will keep this chart updated as information comes in, for as long as this “situation” lasts.

(PRRA Numbers should start filling in soon)